It’s been weird times lately. I went to my usual Wednesday night meditation at my church, where we just sit around in silence for an hour, don’t do shit. It’s my favorite time of the week, pure silence, surrounded by people I love, in this blissful detached embodied peace. There’s not much like it. But this time, it didn’t work so well. My throat kept closing up, like I was about to have a panic attack. The sanctuary felt way too hot, stuffy almost, like I couldn’t breathe. I nearly ran out of the place twice, just to get some air. I couldn’t relax, I couldn’t settle in, I couldn’t pray. But I let the bad feelings pass, just watched them float away down the river, and I made it through to the end. Even stayed for Compline, the best part of the evening. But after what normally is my great relaxer, I felt like I’d just run six miles, exhausted.

That’s why I was really happy I had theater plans with my friend Thomas the next day. Thomas is my favorite guy to go to plays with. He’s absolutely open. I mean, it’s unreal. He approaches a play or a show or a movie with no barriers, ready to receive. That’s not to say he isn’t critical. Thomas brings with him his own very particular standards, pet peeves, strangenesses. That’s what makes him such a good observer. He comes from a place all his own, with his own aesthetic criteria. They are unlike anybody else’s, they’re consistent, and they can be exacting. But again, he’s got his arms open, and he’s ready for anything. Primed for the experience. I love seeing things through his eyes.

The play on the docket this evening was Matt Gasda’s Doomers, at an art venue in Manhattan, instead of the usual BTCR in Greenpoint. I’d been to the space before for my friend Kelsey’s art market, so I was a little bit prepared. When we sat down, a horrible grinding noise sounded from the right-hand wall, which apparently was the restaurant next door doing some drilling. This noise would continue throughout the play, which was fine with me. I love shit like that. Most of the best artistic experiences in my life came with venue issues, from electrocuting microphones to rats running over my feet to brawls over a mechanical bull to drug overdoses on the third row. I remember one of the happiest shows I ever played in my life was at a venue where, when we showed up for soundcheck, the owner let us in, holding a sledgehammer. We watched him proceed to knock down a (load-bearing) wall near the stage to make more space. The whole room was filled with white cancer dust for the entire show. I was spitting up gray sludge for days. It was incredible.

After a lighting mishap, the play got going in earnest. It’s set around two office rooms, with the kind of claustrophobia that reminds you of The Exterminating Angel. The first act is the just-ousted Sam Altman character ranting about the great hope of an artificial intelligence greater than us, while everyone around him scrambles, wanting to believe in their prophet but also wanting to keep their jobs. The second act is the boardroom of the company that ousted him, trying to figure out if they made the right choice, if there was ever even another choice to make.

The thing is, the play’s really funny, genuinely so. I also couldn’t help but get a kick out of the crowd, who mostly seemed to be tech people. The couple next to me were introducing themselves by the software company they worked for, asking others the same. It reminded me of going to tailgate parties in college and stealing food before they found out you weren’t in a frat and kicked you out. There was a thrill to the whole thing.

Afterward, Thomas and I went to a nearby bar to hash the whole thing out. This, as always, is the best part of the night. We both agreed the play was great, though, as always, we agreed at a slant. We both loved that the play didn’t arc so much as mirror itself. The double board rooms, the double blonde CEOs, the double takeout. The fear, the optimism, the arrogance, the substances. The way Gasda is so good at showing people as they are—ridiculous, absurd, a little pathetic, but still very much human, with souls, and capable of great beauty, whether they choose to acknowledge that or not. We both loved the ludicrous doomsday Substacker. Our favorite was the over-it board member who thought this was all overblown, that AI was just another porn generator, that it would be bots making porn for bots. We loved the twenty-five-year-old millionaire zoomer in the Green Day t-shirt. We thought the ousted tech genius was a fantastic character, well-acted, even if we both wanted to punch him in the face the whole time, even as we begrudgingly admired him. (Maybe shamefully admired him?) We argued about his arrogance, whether it was worth making something beautiful no matter how many people you hurt along the way (in the play, the casualties could number in the billions). We talked about Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises and the Richard Brautigan techno-utopian poem “All Watched Over By Machines Of Loving Grace.” We talked about the music scene back home in Mississippi, how much fun it was to have $150 rent and endless time to make things, how much we enjoyed it, how we had no idea how precious and rare that time would turn out to be.

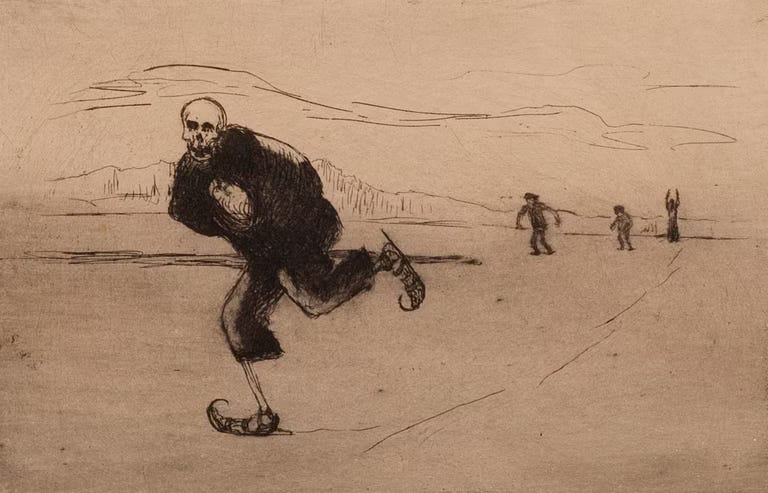

Thomas has been through his own share of tragedies, the death of his best friend, a broken back, the fire that destroyed his apartment last year. He also loves his infant daughter more than I’ve ever seen anyone love anything. He has worries for her future, for the world he brought her into. But he’s still Thomas, and he has that openness, that optimism, no matter what comes his way. For my part, I don’t share it. The world seems to be in mid-plunge, and frankly, AI scares the shit out of me. Not that it’s a demonic power coming to destroy us, but that it’s just some half-assed tool for putting money in already-rich people’s pockets, to the great detriment of everybody else. The way the internet seems hell-bent on turning everything into one of those interstate exits where it’s always a BP and an Exxon and the same four chain stores, no matter what state you’re in. But again, there is also the whole world ending thing, no matter how unlikely. Every bomb wants to go off. That’s what they’re built for. But we’ll see, I guess.

We talked for two hours, our glasses long empty, and it was time to go. We hugged, he got a car, I walked to the subway. I got distracted walking back, took a wrong turn. Saw a couple making out on the sidewalk, rats barreling by, a homeless man on a blanket snoring, a half-eaten pretzel by his side. Barely made my train, but I made it.