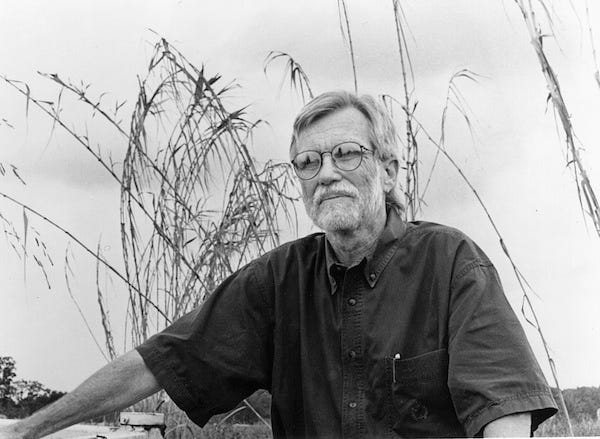

My favorite writer of all time is Lewis Nordan. Not a household name, nor will he probably ever be. Too Southern, too strange, too loving, too horrific. And in a lot of ways, despite the oddness, the magic, all that, too real. I love his books. Deeply. There’s nothing in the world like them.

The best is, without any doubt, Music of the Swamp. A linked story collection set in Arrow Catcher, Mississippi, a kind of phantasmagorical version of Nordan’s hometown of Itta Bena, it follows Sugar Mecklin from a broken childhood to a wounded adulthood, surreal and painful and brimming over with the impossible. The book contains everything I love and hate about the South, and probably everything I love and hate about life as well. It’s a masterpiece. Nordan leans heavy into the Southern cliches, into sentimentality, into the supernatural, and somehow sticks the landing every time. It’s a magic trick. I still don’t know how he did it.

The best story from Music of the Swamp, “Owls,” works beautifully as a standalone, though it obviously gains power from its place in the collection, the epilogue, the final word on the matter. There used to be a video online of Nordan reading it at the Oxford Conference of the Book in 2006. I wish I could find it. You couldn’t see me, but I was in the crowd, seated next to the writer Jack Pendarvis, crying my eyes out.

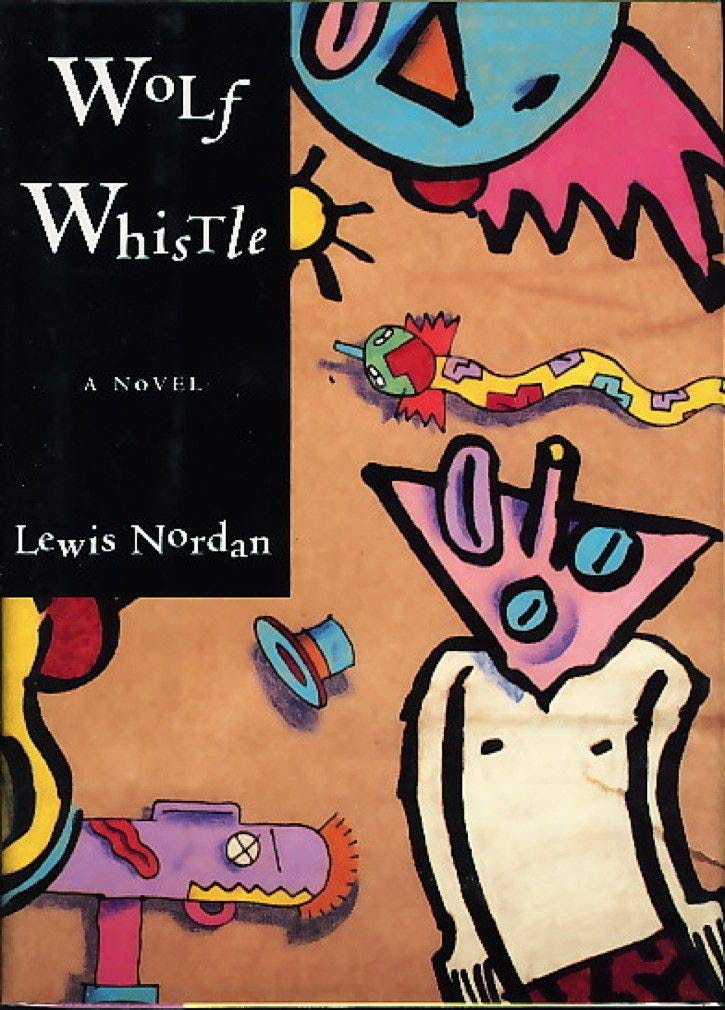

But right now I want to talk about Nordan’s second novel, Wolf Whistle. It’s sort of an impossible book, a metaphysical retelling of the murder of Emmett Till. It’s a beautiful, problematic, infuriating nightmare vision, and I don’t really even know if Nordan pulls it off, or if anyone could. But he swung hard, and the feat itself is worth the ticket. I guess you could classify it as magical realism, but that’s a term so fraught I don’t really want to deploy it here. Regardless, it’s far more Jodorowsky than Garcia Marquez, and there’s no better example of that than the opening section, which sort of functions as a short story all its own.

The novel begins with schoolteacher Alice Conroy (niece of Runt Conroy, of Music in the Swamp infamy) taking her class to visit their “injured” schoolmate Glenn Gregg. The precise nature of Glenn’s injury is withheld until the end of the story, because if it wasn’t, no one would keep reading, it’s too horrific. The writing could almost feel like a children’s story, if it wasn’t so vicious, with Nordan letting people express things they normally could only feel but never put into words. In some ways, he’s translating for us.

Take this brief scene with Alice talking to her students about their classmate’s tragedy:

“Don’t hold back,” she told the children, her fourth graders. “Ask anything you like.”

So they said, “Is he dead?” and “Is he still on fire?” and “Am I going to die?” and “Are we all alone in the world?”

Alice takes the class to the neighborhood of Balance Due, a neighborhood rendered surreal by its own pain and violence:

Filthy, violent men in shirtsleeves sat in the doorways. They staggered, they leered, they drank out of sacks, they worked in muddy yards on junker cars with White Knights bumper stickers. Bottle-trees clanked in the breeze. A hundred-year-old voodoo woman wearing a swastika stirred a cauldron above a fire in a yard nearby. A young man tried to convince a woman, a girl really, to let him shoot an apple off her head with a pistol.

At the Gregg’s house, nobody answers the door. Alice leaves the get-well cards behind. A few days later, Glenn Gregg’s mom writes to Alice asking her to bring the whole class to see him. A few days later, when the children arrive, Mrs. Gregg, who up until this point in the story has had a speech impediment so severe she could not speak, begins talking perfectly, beautifully, without ceasing. Reality, in its own way, becomes too much to bear, and the world starts to crack:

She talked about the weather. She talked about the local arrow-catching team, its prospects for the playoffs…She spoke of more astonishing things, of the difficulty of having a physical handicap, the stammer that she had so recently been silenced by, the loneliness, alienation, the shock of being so afflicted in adulthood… Then, if that were not amazing enough, she told of marrying young, of her disappointment in marriage, of never having danced with her husband, or any man. She told of her failed dreams of romance and the joyless mechanics of sex.

Alice’s reaction, given in another one of Nordan’s signature lists:

When Mrs. Gregg spoke, winter scenes, unlike anything Alice had ever actually observed in tropical Mississippi, appeared before Alice’s mind’s eye. Snow fell through forest trees. One-horse open sleighs jingled along country roads. Chestnuts roasted on open fires. City sidewalks were dressed in holiday decorations. Little hooves clattered upon rooftops. Corncob pipes and button noses would not be suppressed…

Mrs. Gregg unspools her life’s woe while the children inexplicably begin blurting out lines from Christmas carols.

The story plummets onward, and what happened to little Glenn is revealed in its all its horror, and the lack of hope feels complete. It’s nearly unbearable. And in the book, only more, and greater, tragedy will come.

But here’s a thing I skipped over. Right before Alice and the children get to the Greggs’ house, right when they enter Balance Due, a miracle happens, in a single, surreal, perfect sentence:

A skinny yellow dog dragged a saddlebag full of harmonicas down the street in its teeth.

Some days, that’s my favorite sentence I’ve ever read. The strange grammatical construction, the misplaced modifier, the sheer absurdity of the image. I mean, why would a saddlebag ever be full of harmonicas, and why the hell is a dog dragging it down the street? Could a dog, much less a skinny one, drag a saddlebag full of harmonicas through the street? How much does a saddlebag full of harmonicas weigh, anyway?

But that’s why the book works. The dog is both a warning and a promise. That life doesn’t make sense, that beautiful and terrible things happen, that miracles and wonder exist alongside hideousness and tragedy, that love and evil intertwine and fight and find themselves often staring the room across from each other, having completely switched places. Nothing makes sense, not really. Maybe it never will.

In that confusion and strangeness, we are never without hope. Not that what is wrong will be set right (can that ever happen?), but that new goodness can bloom, that at the very least the beauty of the world can sit alongside the horror, can help nurture it into something better. Maybe? I think so. It’s worth believing, anyway. As Nordan writes toward the end of the novel:

The child said, “When you die and get buried in Mississippi, are you still, you know, in Miss-sippi?”

His daddy said, “Naw, honey. That’s the whole point about magic. God is good, it don’t matter how it looks on the surface of things.”

So, yeah, read some Lewis Nordan books. You can get them used for like $4. I mean, why not?

Your previous writings on Lewis Nordan are why I read Music of the Swamp, which I loved. Loved it so much I sent a copy of that book to my writer friend on death row, and now he loves Lewis Nordan too. One of Mississippi’s best “unknown” writers.

I hope you know how happy this post makes me! Beautiful.